Control of access to ourselves in the sense of our personal information. Privacy is the ability we have to determine what others know about us.

Most of us don't have a problem with letting others know our name, or see the image of our face; anyone with a Facebook account is more or less conceding that this is open information. But, there are closer details we restrict to friends and familiar others: a phone number, a home address.. Some fewer things are known only within the family. Then, there are thoughts, fears, and desires kept to ourselves.

Privacy doesn't correspond with any one of these personal exposure levels; it has nothing to do with the specifics of who knows what. Instead, it's the power to create and maintain the exposure distinctions: privacy means you control who knows what.

Access to ourselves involves our:

It is all the ways that we can be conceived as individuals.

Privacy is not a synonym for secrecy; privacy is the ability to decide what remains secret, and from whom.

Privacy does not mean the right to be left alone. A private moment may be solitary, or it may involve many others (a wedding, a funeral). Either alone or accompanied, privacy exists when you determine who’s there.

The loss of privacy is exposure, which does not mean that others access you, but that you are vulnerable to their explorations.

Privacy isn't something we have, it is something we do. It’s not a possession, it is an ability, or a power.

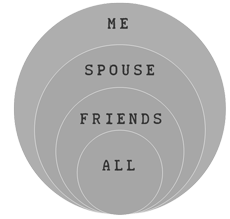

Privacy’s traditional conception pictures concentric circles. The one individual occupies the outermost circle, meaning he or she has access to all information. The next interior circle might hold a spouse, who has access to all but the individual’s most intimate knowledge. Then the family, and a circle for friends, and finally the open space of society. Those inhabiting each ring have access to everything within their circle, but cannot penetrate the information outside.

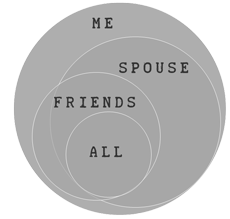

The reality distinct, it's a less symmetrical distribution of information. While it remains true that for each person only the one has access to all information, after that, others occupy contoured shapes of access: a friend may have access to details of the past that even a spouse is denied, while other information is accessible for the spouse but not the friend, and so on.

Privacy functions defensively – the ability to shield ourselves from prying eyes – but it's equally true that privacy requires the positive ability to share information: you don't control what you can't distribute.

So, theoretically, there are two zero-privacy extremes. At one end, you are completely exposed: you cannot hide anything, from anyone. At the other, you are entirely muted and alone: you can disclose nothing, to no one. Either way, you have no privacy because you have no control over access to yourself.

One efficient way to deal with privacy is to say it’s over.

There are four versions of the end:

Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy notoriously claimed, “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.” The problem with asserting that we should get over wanting privacy is what’s at stake: privacy isn’t just about personal information, it’s also a power, the ability to restrict access to ourselves. So, accepting a zero-privacy reality means more than surrendering all secrets, it also implies surrendering the ability to not surrender. That’s a lot to lose.

In sum, the argument is that even if we have zero privacy, we shouldn’t just get over it because that means giving up even more. This point is sometimes made in the general terms of what’s called an is/ought distinction. Facts don’t automatically convert into moral imperatives: just because we don’t have privacy doesn’t mean we ought to stop trying.

Google CEO Eric Schmidt notoriously suggested: “If you have something that you don't want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn't be doing it.” The problem is that privacy doesn’t just hide moral blemishes, it’s also required for each of us to select how we present ourselves to the world. There’s nothing morally embarrassing, for example, about flipping through pictures of yourself to select which ones you want to display on, say, Tinder. That’s the way you show others who you are, and who you’re not. (That’s why you don’t include snapshots from the 70’s disco party you went to for New Year’s.) But the entire effect is ruined if others can freely thumb through all your pictures, or whichever ones they choose.

Privacy, in other words, is a positive ability more than a shelter for delinquency and perversion.

Vinton Cerf, one if the true inventors of the internet, proposed:

Researchers support him. Especially with respect to habitational space in western societies, partitions we consider salutary are, in historical terms, fairly recent. Until the 17th century, for example, even aristocrats commonly shared a sleeping room with non-intimate others, including their servants. If that’s right, the reasoning goes, then the unveiling of all our personal information for all the world to see on the internet is not a deviation from the historical norm, it’s a return. It’s normal for people to know a lot about others.

Of the arguments against privacy, this is the most interesting. That doesn't save it from being fundamentally misguided. The problem is a basic misunderstanding. Privacy is an ability, not a dataset. It’s the power I have to control access to my information, not the absence or presence of my personal information in the public realm.

So, it may be true that social media platforms including Tinder stockpile countless bytes describing each user, and it may be that more esoteric databrokers buy and then trade that information. But, there’s no necessary correlation between that accumulation, and the answer to the question about whether privacy exists. The stockpiling only invites a question about consent: Do users care whether the platforms gather and trade their data? Do they agree to allow it? If they do, then there's no reason to think that privacy has gone out of style.

The most sophisticated reasoning against privacy is that it overcomes itself as transparency. The structure of the argument is familiar to philosophers, and starts from the observation that many concepts carry within themselves a kind of inflection point or vulnerability, that is, a point where the kind of thinking that presumably supports the larger idea actually corrupts it.

One of the oldest examples comes from medieval theology. The argument starts from the premise that God is all powerful, and pushes in various directions (God can part the waters of the sea, God can flood the earth) until reaching a question like this: Can God make a boulder so heavy that He can’t move it?

An analogous inflection point exists at the core of rights theory. The critical question is: Can you sell yourself into slavery? This is a dilemma because the ethics of rights is built on freedom maximization: Everyone can do whatever they want, up to the point where their free acts interfere with the freedoms of others.

So, if the basic value is freedom, the question arises: Is my freedom so great that I'm free to cancel it?

Does the question even make sense?

It's hard to know.

Regardless, a similar dilemma rises around privacy. If privacy means control over access to my personal information, can I control by deciding to not control? Does my own privacy grant me the right to allow pure transparency?

What's at stake here is the possibility of a transparent self. Instead of thinking about data accumulation and algorithmic capitalism as antithetical to privacy, they serve the purest version, the one where control over access to ourselves maximizes (or overcomes itself) as total access for all.

Here are some of the questions surrounding the possibility of the transparent self.