The material of small data is indistinguishable from the substance of big data. Both compose from numbers that measure (age, height, weight), words that describe (gender, race), directions that map (my phone constantly transmitting my movements), colors that shape (the color of my car, my house, my shirt), sounds that resonate (Amazon’s Alexa hears when I'm scolding my daughter), desires that impel (Google knows my searches), and all the rest that we can render as descriptive and predictive of humans in the world.

Small data can be processed biologically; big data must be subjected to tables that organize, formulas that quantify, and then electric algorithms that render.

Information increasing past human comprehension in three directions: Volume, Velocity, Variety.

Titan supercomputer (Oak Ridge), calculations per second: 27,112,500,000,000,000.

Variety comprehension threshold not yet crossed.

Transparent pools of data derive from explicit exchanges of personal information for services. Instead of paying with cash, you sell a layer of yourself: privacy becomes a currency.

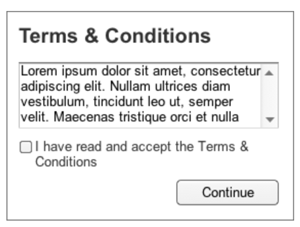

The privacy debate surrounding transparent data pools involves informed consent. It's true that users check the small box acknowledging their acceptance of the terms of service before we download the app or before our account is activated, and so we all know, on some level, that we're willingly trading away our personal information, but questions remain:

In dark data pools, third parties purchase information from direct collectors, then combine and process the data into richer profiles, before selling back into the consumer-oriented marketplace.

In both economic and human terms, datasets don’t accumulate as addition, but as multiplication. When information about different aspects of your life gets put together, the emerging profile can be very telling.

The privacy debate surrounding dark data pools involves ownership. When you download an app after trading a layer of privacy for the convenience, are you trading:

There's a legal answer to this question (check the small print in the service agreement), but the ethical question involves the relation between individuals and the information describing them.

It could be argued that the bond between me and my data resembles the one between me and my biological life: the data can't be entirely separated from what it means to be me. If that's persuasive, then I maintain some claim on my personal information regardless of the boxes I’ve checked. Like my life will always ultimately be mine, so too the data that describes my life.

By contrast, if the information is conceived as something I fabricate, like a carpenter makes a chair, then when the data is sold, whoever acquires it bears no responsibility to the originator. (It has never happened that a carpenter barged into a client's house and asked for his chair back because the owner decided to paint it a different color.)

There is a curious middle ground. Sometimes artists will object to uses made of their works, and architects will object to remodeling efforts they view as crudely destructive of their buildings. Probably there's no legal force behind the protests, but they may find traction in human terms.

The elementary content of small data is indistinguishable from big data (numbers, words, directions, colors, sounds, desires). But, as the volume of information and the velocity of processing surge past human comprehension, the experience of the material changes.

The historical analogy is Zeno's paradox, but the contemporary comparison is the movement from still images to video. When a string of images are racked and flipped at a rate of 30 frames per second, what we see is not a vast number of individual pictures at a very high speed. Instead, something radically different. The single video is other than the frames; it’s not an evolution, it's revolution, a different kind of vision and reality.

There’s a threshold: the volume and speed of the individual images increases until the sequence collapses back into the unity. Multiple pictures become a single video.

Similarly in the movement from small to big data: it's not more of the same, only faster. It’s a threshold. Big data doesn't evolve from small data experience, instead it's a leap into a different reality.

Small data is information humans can comprehend.

There is one exception: art. Any single true piece of art is small data bursting with significance that exceeds human comprehension: it always escapes full understanding, that's why we can always return and see something new each time.

So, along one vector, art can be partly defined as this paradox: small data that surges to big data, but without the addition of superhuman velocity/volume/variety.